The author with Sammy Davis at his home in Southern Indiana

by Norman Fulkerson

This is the story of Samuel L. Davis who earned the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Vietnam War. When his 42-man unit was attacked by a 1500 man Vietcong battalion, he refused to give up. After suffering a broken back and perforated kidney, he was not only able to repel the enemy, but carry three men to safety, AT THE SAME TIME. One of the defining moments in his life was the noble way he endured the ungrateful treatment upon his return home.

Bowling Alley

Born November 1, 1946 in Dayton, Ohio, Sammy Davis’ family eventually moved to southern Indiana where he graduated from Mooresville High School. During his junior year, he worked in the lumber industry taking down 200-foot white pines. This not only provided pocket money, but also contributed to an upper body physique one commonly associates with lumberjacks. All in all, Sammy was pretty much your garden variety, hard-working, Midwestern boy living an average existence in America’s heartland.

Colonel Roger Donlon, on the day he received the Medal of Honor, was an inspiration for Sammy Davis

All of that changed, during an evening with friends at the local bowling alley. Above the din of smashing pins, Sammy’s attention was momentarily drawn away from the game to watch a news item that piqued his interest: Colonel Roger Donlon was being awarded the Medal of Honor by President Lyndon Johnson, for his heroism in Vietnam. It was not so much the fame and glory of the event that attracted Sammy, but the way Colonel Donlon stood so straight and tall as he received our nation’s highest honor.

“I want to grow up to be just like him,” he said. “I want my daddy to be proud of me.” It did not take long for him to act on this good inspiration. At seventeen, he decided to join the Army. Before he left for basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, his father who had fought in World War II looked at him and said, “Son, now it’s your time to serve.” After finishing advanced artillery training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma he was sent to Vietnam in March of 1967 as a Private First Class.

Eight months later he would accomplish a feat that would make his father and the nation very proud.

“Go, Kill the GI!”

For a small-town boy from Indiana, war was a different experience. Three days after arriving into Vietnam, he received a baptism of fire when the Long Binh ammunition dump was blown up by member of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). It was the largest such storage facility in the world at that time. Private Davis or “Dave,” as his fellow soldiers called him, remembered the experience of unexploded eight inch rounds landing all around their compound. Although this caused him no small amount of alarm, it was nothing compared to the life-defining battle which occurred later that same year.

Sammy Davis in Vietnam, the year he earned his Medal of Honor

On November 15, Private Davis, forty-one other soldiers and four 105mm howitzers were dropped into a swampy area known as The Plain of Reeds: a vast wetland located in the southernmost portion of Vietnam along the Mekong River. Their mission was to provide close and continual artillery support for infantry units fighting hard to push the advancing Vietcong back over the border into Cambodia. Their home for the next days was Fire Base Cudgel, during an operation code named Coronado One.

Just before five in the afternoon on November 17, Sammy remembers very well the arrival of a helicopter. On board was an officer who informed the men that there was a 100% probability they were going to get hit that night. Since arriving in the area on November 15, they had already seen a plenty of action. Therefore, it was hard to fathom what this officer was speaking about. Private Davis figured it would be pretty much the same and regrets they were not given more details.

As darkness surrounded the sleeping members of Fire Base Cudgel, the man pulling guard duty that night was finding it hard to stay awake. Private Davis was having the opposite problem, and agreed to relieve him fifteen minutes before his own scheduled 2:00 a.m. shift. Minutes later, he heard the ominous sound of mortars sliding down metal tubes, followed by a mortar attack which lasted for half an hour before stopping abruptly. Private Davis described the silence that followed as “unearthly.” The stillness was suddenly broken by the sounds of whistles and bugles. With the order to charge, 1500 enemy soldiers began screaming in broken English, “Kill the GI!” The intensity of the battle over the next four hours defies description.

An example of the Fleshettes which pierced Sgt. Davis' body

Surviving “Soldier Hell”

Sammy Davis immediately began firing beehive rounds from his 105mm howitzer. This particular shell, containing 18,000 fleshettes that look like miniature spears, virtually turns the howitzer into a gigantic shot gun. After several rounds, the NVA were able to zero in on his gun, by aiming their rocket propelled grenade launcher at the muzzle blast. Their first round of retaliation was a direct hit on the Howitzer which threw Private Davis, now unconscious, back into his foxhole. His commanding officer simply disappeared into the night.

The remaining members of the decimated unit, located behind Private Davis, attempted to stop the advancing enemy. They fired off another beehive from their howitzer which struck Sammy Davis in the back as he lay unconscious. The impact would have killed him if not for the flack jacket he was wearing. When Davis finally regained consciousness, he was laying face up in the fox hole with dozens of wounds from fleshettes that had pierced his body. One of them perforated his kidney, while another lodged in his fourth vertebrae, causing intense pain. The explosion left him temporarily deaf and during the momentary silence, he began to marvel at the multi color tracers, illuminating the sky above him. “Wow,” he thought to himself, with childlike candor, “that looks just like Christmas lights.”

Seargent Sammy Davis made it through that fateful night by remembering a simple phrase: "You don't lose until you quit trying."

As his hearing returned, so did the noise and chaos of battle. Six feet in front of him was the canal with hundreds of enemy troops, at a time, coming through the water to finish what they had started. At this point, Private Davis, thinking he was alone, became a solitary “line of defense.” With a shattered howitzer and little hope of resistance, he clearly remembered thinking, “You don’t lose until you quit trying.”

With this inspirational thought running through his head, he grabbed an M-16 and fired it till he ran out of ammunition. He then found an M-60 and 1000 rounds. As he shot through the first 500 rounds a human wave of enemy combatants continued to come at him, like bees from an agitated hornets’ nest. Seeing the apparent futility of resistance, he struggled with the strange thought that perhaps his gun was not working. By the time he reached the end of the 1000 rounds something even more bizarre crossed his mind.

“I figured I had died and was in ‘soldiers hell,’ ” he said, “and this torturous circumstance was going to last forever.”

Refusing to quit, he looked skeptically at the smoldering howitzer. Although it was badly damaged he felt certain he could get off another shot. Not too concerned with precise measurements, he crammed it full of powder, loaded another beehive and quickly pulled the lanyard. All he heard, in response to his efforts, was a pathetic “poof” sound, giving the sinking impression of wet powder.

Anticipatory excitement soon followed as the big gun began to convulse like a shuttle ready to blast off. The maximum load, for a fully functional howitzer, was a seven charge. They would later estimate Private Davis had given his a twenty charge.

When the gun finally fired, it reared up in the air and off its wheels. The subsequent explosion and burst of fire was so violent that the rest of the men screamed with joy thinking Private Davis had rigged up some kind of hellish flamethrower.

Sammy L. Davis is honored by USA Stabilization Force at the dedication ceremony for the Headquarters building named in his honor at Eagle Base, Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

“Way to go Dave,” they screamed. As they were jumping with joy, Private Davis was writhing in pain. He had been thrown to the ground by the blast and the two-ton howitzer landed on his back, breaking his third lumbar vertebrae. The swelling caused by the injury pushed against his spine provoking a numbness in his legs.

However, as bad as things were, he was about to face his biggest challenge of the night; rescuing three soldiers caught on the opposite side of the canal.

“You Never Leave a Buddy Behind.”

In spite of the severity of his injuries, Sammy Davis was somehow able to fire three more beehives before hearing, what sounded like an American soldier shouting for help. “Don’t shoot, I’m a G.I.,” the person screamed from across the canal. American servicemen were warned to treat such cries with suspicion. The enemy had learned to say the same thing, in perfect English, as a way of drawing them into an ambush. Nevertheless, after firing an illumination round, Sammy Davis clearly saw the individual, frantically calling for help, was a black man named Gwendell Holloway.

With a broken back and his energy almost gone, Private Davis grabbed an inflatable mattress and began to cross the canal, as bullets pelted the water all around him.

Arriving on the other side, he found three members of a recon unit commanded by Lt. Lee Alley, who narrates the night’s events in his book Back from War. Gwendell Holloway, Billy Ray Crawford were both badly wounded, but the third man, Jim Deister, lay lifeless after being shot point blank in the head. The bullet entered the ear and, it was later determined, lodged in his brain: very much like the fatal shot inflicted on President Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. Sammy was forced to perform the gruesome task of pushing Jim Deister’s oozing brains back into his head.

Jim Deister center with his nephew, Slade Deister (far left) at the Dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Pittsburg Kansas State University, owes his life to Sammy Davis (far right).

With the battle still raging, Private Davis reasoned that three separate trips to get the wounded to safety would be risky. To carry all three at the same time seemed virtually impossible. But after “calling on help from above,” that is exactly what he decided to do.

“When I was little,” Sammy Davis says, describing his actions, “and we would go out to play, my mom would always tell us, ‘now don’t leave your brother.’ It was the same way in the Army. I wasn’t going to leave my brother behind.”1

With iron resolve, he placed the limp body of Jim Deister over his shoulders. He then grabbed the other two, one in each arm, and began to make his way back to the canal. Periodically he was forced to stop, when a group of enemy soldiers passed. He would then lay his men down in the tall elephant grass and cover them, very much like a protective mother hen. Whenever the enemy noticed they were alive, Sammy was forced to silence them.

After arriving to the other side of the canal he put the wounded soldiers on the helicopter and after placing the lifeless body of Jim Deister among the KIA (killed in action) he collapsed from exhaustion. As the chopper slowly ascended, the medic looked with astonishment at the soldier with the horrifying head wound. Jim Deister was actually breathing. They immediately began tending to his wounds and, although no one could figure quite how, he ultimately survived.

Sammy Davis was eventually promoted to corporal. Although he endured that battle, he would face another, almost as painful, upon his return to the United States.

“To Get to Your Aircraft You Have to Run the Gauntlet.”

It occurred on the day Sammy Davis was about to board his final flight in San Francisco, the last leg of a very long trip home to Indiana. One can only imagine his joy at being reunited with his family after the horrors of war and the pride for having served his country admirably. His father would no doubt be proud of him, but others would not.

Milling around in the San Francisco airport were a group of twenty hippies. In order to circumvent the laws forbidding clubs, all of them pretended to be disabled, and carried canes instead. They also had brown paper bags full of what Corporal Davis described as the “nastiest things you can think of” such as “dog droppings.”2

It is hard to find a more striking contrast that the one that exists between a man like Sammy Davis and Hippies of the 60's.

Although Sammy and two other servicemen were dressed in civilian clothes, as instructed for those on commercial flights, their military bearing made them clear targets for revolutionary aggression. One soldier reminded Sammy of the specific orders given by their sergeant, back at Travis Air Force base. They were explicitly forbidden to retaliate, should someone start an altercation, since the media would inevitably spin it against the returning soldiers.

“Hey, if you want to get to your aircraft,” one of the hippies said, “you have to run the gauntlet.” Seeing the scene before him, Sammy Davis said he and his fellow soldiers decided they would not run the gauntlet, they would walk it: and do so with pride and dignity.

The first hippies began rubbing the contents of their bags in the soldiers hair, on their face and stuffing it into their ears. When they failed to get the desired response they began beating them with the canes which opened up head wounds, causing Sammy and the others to bleed profusely.3

This was the despicable treatment for a man who proved himself on the field of battle to be one of America’s great warriors. Yet through it all, Sammy Davis accepted these injustices with dignity and kept his composure till the end.

It is worth mentioning, for the record, the treatment they received on the plane. Solicitous stewardesses gratuitously seated them in first class, served them champagne, cleaned their shirts and wiped the blood from their head and faces.

Where They are Today

Because of his injuries, and the lingering effects of Agent Orange, Sammy Davis was forced to retire from the Army in 1984 with the rank of sergeant. Besides the Medal of Honor he also earned a Silver Star and two Purple Hearts.

After being medically discharged from the military, Jim Deister returned to college where he earned a Bachelor’s of Science in psychology and later a Master’s in Rehabilitation Counseling. He now resides in Salina, Kansas where he works as a counselor for the deaf and hard of hearing for the State of Kansas, in 18 different counties.

Jim Deister (right) with his friend Sammy Davis at the dedication of a War Memorial in Salina Kansas. Jim Deister was able to go on because he learned, from Sammy, that one must not only be willing to die for their country, but also to live for their country.

When people ask him about retirement, his response is always the same.

“I will retire,” he tells them, “when my secretary, comes in and finds me dead at my desk.” If not for the speech impediment, one might never know the trauma he endured. There are two reasons for this.

First of all, he detests the way Vietnam veterans are often portrayed in books and movies, with what he calls, the “victim syndrome.”

“The majority of us did our duties,” he says, “then we came home, went to work and raised our families.”

The second reason is more personal. Mr. Deister recognizes that Sammy Davis not only saved his life, but gave him the inspiration to go on living. He received this motivational nudge from one sentence in a speech given by his friend, which moved him profoundly. “You not only have to be willing to die for your country,” Sergeant Davis often tells audiences, “you must also be willing to live for your country!”

“That particular phrase sort of shocked me out my guilt feelings,” Mr. Deister admitted, “and I told myself that yes, that means me. I am alive, now I have to live for those men who were killed that night.”

Today Sergeant Davis lives a simple life amidst the corn fields of southern Illinois. He is a member of the Medal of Honor society along with his boyhood hero Colonel Roger Donlon. He continues to give an average of 300 inspirational talks around the country each year. In spite of the ill effects of war, he accepts his sufferings with patience and calm. However, he will candidly admit that memories of November 18 still haunt him, but quickly adds, “Its only been 41 years. So tomorrow night will surely be better.”4

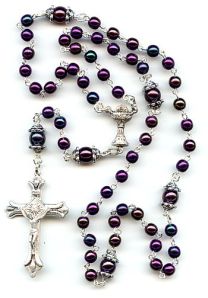

The Congressional Medal of Honor

In spite of everything he has accomplished in life, Sergeant Sammy Davis retains a refreshing humility and, one could say, almost boyish simplicity. It is not hard to imagine how such a man could think about Christmas while contemplating the multi-color tracers during a hellish firefight in Vietnam: perhaps that is what makes Sergeant Sammy Davis so special. Not one for complicated formulas, he sees life through a different prism. It was for this reason that he was able to overcome life’s toughest battles. He knew that you really don’t lose until you quit trying.

1. http://blogs.uiowa.edu/jmcglobal/2010/03/05/the-real-forrest-gump [back]

2. http://blogs.uiowa.edu/jmcglobal/2010/03/05/the-real-forrest-gump [back]

3. http://www.pritzkermilitarylibrary.org/medal-of-honor/ [back]

4. http://www.courierpress.com/news/2008/jul/05/soldiers-tale-of-uncommon-valor [back]

![medal+winner+xavier[1]](https://modernamericanheroes.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/medalwinnerxavier1.jpg?w=223&h=300)