You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Col. John Ripley’ tag.

Marine Corps Body Bearers carry the coffin of Colonel John W. Ripley to his final resting place in the Naval Academy Cemetery.

My first exposure to Marine Corps Body Bearers was at the funeral of Colonel John Ripley. Below is a very interesting article about the men who have the honor to carry fallen heroes to their final resting place. The next time I saw them was at the funeral of Colonel Ripley’s wife Moline. NJF

by: Cpl. Scott Schmidt | Tuesday, June 29, 2010 10:56

WASHINGTON – It’s an iconic scene: Six men stand together halfway around the world from home and raise a flag on top of Mount Suribachi. When the men returned home, their story of valor on Iwo Jima lifted a nation to its feet in the midst of the turning point of World War II.

Now, more than 60 years later, another six Marines stand tall in the shadow of the Marine Corps War Memorial’s valor as it depicts that iconic scene.

They belong to the group of 13 Marines who carry the caskets of fellow Marines through the streets of Arlington National Cemetery and surrounding National Capital region cemeteries, (sometimes up to a mile,) as the last salute to the fallen members of the 234-year-old brotherhood.

To read more Click Here.

but I could not pass this story up, since it is along the same lines as the last post about the Catholic Marine.There are those who might consider such religious practices as something incompatible with heroism and the military life. However, true men, see the value of prayer, even AND MOST ESPECIALLY FOR WARRIORS.

Colonel John W. Ripley, to whom this blog is dedicated, screamed “Jesus, Mary, get me there,” when he saw his strength fading under the Dong Ha bridge. He did so because he saw the value of calling upon God (for Whom it is child’s play to create universes) in his hour of need. Colonel Ripley received the Navy Cross for his heroic efforts but readily admitted it would not have been possible without Divine Assistance and was not ashamed to say so in public.

This story is about a British Soldier named Glenn Hockton, who likewise attributes his survival, after two near death experiences in war, to the fact that he carries the rosary. On one occasion he was shot in the chest and his parents still have the bullet which lodged in his body armor. More recently his mother described how he felt like he had been slapped on the back. When his rosary fell to the ground, he reached down to pick it up, only to realize he was standing on a land mine. The ironic thing about this story is that Glenn’s grandfather, who fought in WWII, also attributed the rosary to saving his life, when he miraculously survived an explosion that killed six members of his platoon. If you have not done so already, read the rest of this story by clicking here.

Similar stories have been documented in the articles No Greater Love and The Ideal Soldier.

June 29, 2010 would have been the 71st Birthday of Colonel John Ripley. Although he is no longer with us his memory, as Mary Susan Goodykoontz says so well in this book review of An American Knight, will live on forever.

Mary Susan Goodykoontz at her home in Radford, Virginia with a picture of her brother John Ripley, dangling under the Dong Ha bridge to her left.

“While the world knew my brother John as a Navy Cross recipient, I will always remember him simply as my darling little boy. Being the oldest member of our family I had the joy of caring for him as if he were my own child. It was for this reason that I was overjoyed when Norman Fulkerson contacted me, after John’s death, with the idea of writing a book about his life.

“The final product, titled An American Knight, gave me the chance to see a side of John I frankly never knew. Although I was well aware of his heroism at Dong Ha, I did not know he was such a legend in the Marine Corps, because he did not tell me those things. John was very humble.

“While I thoroughly enjoyed An American Knight and found it to be an extremely accurate account of my brother’s life, it was, at the same time, a painful read since it brought back so many happy memories of someone I sorely miss. I have had, since John’s death, this feeling that he would never die. That is to say that his memory would live forever. Now I know it certainly will because of Mr. Fulkerson’s book. As Irving Berlin, the Jewish-American songwriter said: “The song is ended but the melody lingers on.”

“On behalf of my family, of which I am the last living member, I say thank you!”

Mary Susan Goodykoontz, Radford, Virginia

This first biography on Col. John W. Ripley contains the full House Armed Services Committee testimony he gave against allowing homosexuals in the military.

Not in the Pentagon Closet

by: Brett Decker

Listening to the liberal media, it’s easy to think that all America’s generals and admirals want to torpedo the ban on open homosexuals serving in the military. At times, there is a revolving door on the Pentagon’s closet, with some of the brass putting fingers in the air to test which way the winds are blowing.

While politicized officers might try to curry favor with the Obama administration and congressional Democrats by assuming the liberal position in favor of ending the so-called “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, 1,164 flag and general officers have signed a petition informing President Obama that, “Our past experience as military leaders leads us to be greatly concerned about the impact of repeal [of the law] on morale, discipline, unit cohesion and overall military readiness.”

The extraordinary open letter by so many respected military leaders, which has been shepherded by the Center for Military Readiness, isn’t surprising to most Americans, who know those serving in uniform are among the most forthright in America, a few media darlings aside. However, in our morally confused age, officers who defend traditional values tend to be the ones kept in the Pentagon closet rather than those with less normal views. Despite this political pressure, most warriors espouse a very conservative ideology. One of them speaks to us from the grave.

The late Col. John W. Ripley is a Marine Corps legend for his many heroic stands in combat, in congressional hearings and in life. In “An American Knight,” first-time author Norman J. Fulkerson does a masterful job recounting not only what this great man did, but why he did it and how he became who he was. In short, with a few exceptions aside, great men aren’t born – they are formed. John Ripley benefited from the example of a strict family upbringing and the influence of an ascendant American culture that was unabashed in its encouragement of the eternal verities of God, family and country. In the Ripley household, religion wasn’t only for women and wimps, and the whole family knelt to pray the Rosary together every day.

Painting by Col. Charles Waterhouse of John Ripley dangling above Cua Viet River as Angry North Vietnamese soldiers fire upon him.

It was this faith that would fortify the tough Marine during his toughest trials. His most celebrated feat was on Easter Sunday 1972 in Vietnam, where he singlehandedly blew up the Dong Ha bridge to halt a communist advance along the main transportation artery into South Vietnam. For more than three hours, he climbed the superstructure of the bridge, swinging from steel girders like monkey bars to place explosives and detonators under the main supports. He scaled the bridge over a dozen times, taking heavy fire the whole time, to accomplish the mission and thwart the enemy.

In the years after combat duty, Col. Ripley served in many roles, including stints working for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as an instructor at the Naval Academy in Annapolis and even as president of the Southern Seminary, an all-woman’s college. As the years passed, the Marine’s Marine feared that America was endangered by another leftist threat: political correctness. During the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century, he again answered the call, publicly arguing against admission of girls into the Virginia Military Institute and against women in combat. It was his belief that these positions were in defense of ladies and femininity, especially by trying to protect them from abuse. “If we see women as equals on the battlefield, you can be absolutely certain that the enemy does not see them as equals,” Col. Ripley said. “The minute a woman is captured, she is no longer a POW, she is a victim and an easy prey … someone upon whom they can satisfy themselves and their desires.”

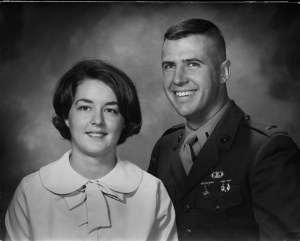

1993 photo of Col. John Ripley. The same year of his heroic testimony against allowing homosexuals in the Military.

Mr. Fulkerson explains that, “While Americans appreciate the warrior spirit of someone like him, we admire much more a person who is not afraid to tell the truth.” That’s why “An American Knight” is not only an interesting book for military buffs but offers inspiring reading for anyone looking for noble examples amidst modern amorality. On the night of Oct. 28, 2008, this Marine met his maker. But while Col. Ripley is dead, his legend lives on. If you listen closely to the din of contemporary political-military debates, the voice of Ripley echoes.

Brett M. Decker is editorial page editor of The Washington Times.

http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2010/may/21/not-in-the-pentagon-closet/

By Debbie Thurman, DAILY COURIER

Saturday, April 3, 2010

This week Christians observed the Passion of Christ, the suffering servant but also the King of kings. Were he still among us, one warrior-servant whose deeply abiding faith and military prowess helped shape him into a legend — a latter-day knight — would be solemnly worshipping. He also likely would be recalling another Easter Sunday 38 years ago at almost precisely this time of year in a quaint but war-ravaged South Vietnamese village called Dong Ha.

In 1972, Marine Capt. John Ripley was in South Vietnam for the third time as one of the last American military advisers. His first two combat tours were as a rifle company commander. He was already the stuff of legend.

Read more by clicking here.

To purchase An American Knight: The Life of Col. John Ripley click here.

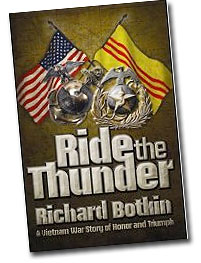

Ride the Thunder: A Vietnam War Story of Honor and Triumph

A Review of Richard Botkin’s Recent Book: Ride the Thunder: A Vietnam Story of Honor and Triumph

A Review of Richard Botkin’s Recent Book: Ride the Thunder: A Vietnam Story of Honor and Triumph

By Michael Whitcraft

One of the most cited and least understood wars in American history is Vietnam. Due to these misunderstandings, it has become synonymous with the words quagmire and disaster.

Thus, opponents of current military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan decry our operations there saying that America is getting itself into “another Vietnam.” However, were US military activities in Southeast Asia really so bad after all?

The answer is yes and no: Yes, they were certainly a worldwide embarrassment as our troops left the field of battle without victory. However, judged by the performance of America’s military, the answer must be a resounding no. Sadly, politicians, not warriors, decided the outcome.

Thus, the true story of the American soldiers’ valor must be told. Such was the task of Richard Botkin in his recent 650-page tome, Ride the Thunder: A Vietnam War Story of Honor and Triumph. In it, he successfully fulfills this task by doing exactly what his title suggests: telling the story of the Vietnam War in terms of honor and triumph.

The book primarily focuses on three Marine heroes: Colonel John W. Ripley, USMC, Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Turley, USMC and Vietnamese Lieutenant Colonel Le Ba Binh. In telling their stories, Mr. Botkin seamlessly intertwines a retelling of the history of the entire Vietnam War. His work is painstakingly researched, yet highly readable.

Certain points stand out among the many details of the book. First, the immense suffering that the Vietnamese people suffered at the hands of the Communists. Mr. Botkin vividly demonstrates this with incidents of the North Vietnamese Army’s (NVA) intentional targeting of innocent civilians.

After the end of the war, more challenges awaited the devastated South, including persecution from their Northern captors. This included the creation of “reeducation” camps throughout the country. Despite their inconspicuous label, these camps had nothing to do with regaining lost knowledge. As Mr. Botkin points out, the installation of these camps “was nothing more than organized revenge on a massive scale.” (p. 548)

Ride the Thunder includes the story of how Lieutenant Colonel Le Ba Binh was forced to spend more than eight years in one such camp, during which time he was allowed less than two hours total visit time with his family.

Another important point Mr. Botkin highlights is the military success the American and South Vietnamese armies enjoyed throughout the war. He convincingly dispels many media-created myths that Vietnam was a lost cause.

The fact is that American forces did not lose a single battle of any consequence in the entire war, in spite of their self-defeating policy that allowed the enemy free communications along the Ho Chi Minh trail and safe havens in Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam. Even the oft-touted Tet Offensive of 1968 was a very real defeat for the NVA.

Despite the operation’s enormous scope, South Vietnamese and American forces had already regrouped and began a counterattack within hours of its first salvos. They were so successful that other than continued fighting in Hue and Khe Sahn, the entire offensive was defeated within two weeks. In Hue, expelling the Communists took twenty-seven days, while the enemy eventual abandoned Khe Sahn as well.

Therefore, the North Vietnamese did not gain any ground and loss an estimated 45-50 thousand troops KIA during the offensive. Many more thousands were captured. (American deaths during the entire war are estimated at around 58 thousand.)

All-in-all, military leadership classified the operation as a tremendous victory. The only Communist victory of the campaign had been fought for America’s soul. As Mr. Botkin described it: “the Communist offensive did achieve a public relations coup with the American public well beyond what a militarily defeated [NVA] could have possibly dreamed.” (p. 146)

However, a Communist operation in March of 1972 dwarfed Tet in size, aggressiveness and overall danger to South Vietnam. Dubbed the Easter Offensive, it began with a simultaneous attack on twelve bases that spanned the entire length of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). From its very beginning, all known friendly artillery positions came under attack.

With American troops already largely withdrawn, the objective seemed obvious and frighteningly obtainable: break through the South’s weak defensive lines and drive southward to Saigon, thus winning the war and subjecting all of Vietnam to Communist domination.

Fortunately for the South, the Communist troops met unbelievable resistance that was greatly aided by the actions of three tough Marine officers who refused to give up.

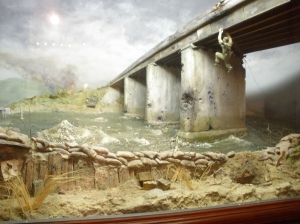

The first was Vietnamese Lieutenant Colonel Binh, whose battalion (known as Soi Bien or “Wolves of the Sea”) held the ground defending a bridge across the Cua Viet River at the city of Dong Ha. The bridge was highly strategic because it was the only crossing in the area sturdy enough to support the more than 200 tanks the NVA had assembled on the north side of the river.

Lieutenant Colonel Binh persistently held his ground in spite of overwhelming odds. It was his training and leadership that kept the situation together in Dong Ha as his men faced the fight of their lives.

The Lieutenant Colonel’s determination is well demonstrated in a radio message he sent out to his commanders when rumors began to circulate that Dong Ha had fallen. He said:

It is rumored that Dong Ha has fallen…My orders are to hold the enemy in Dong Ha. We will fight in Dong Ha. We will die in Dong Ha. We will not leave. As long as one Marine draws a breath of life, Dong Ha will belong to us. (pp. 327-328)

While the desperation of the situation led scores of South Vietnamese troops throughout the DMZ to desert, not a man of the Soi Bien left his post.

Their efforts supported American Colonel John W. Ripley, then serving with Colonel Binh as an advisor. He would need all the help he could get as he took on a mission to destroy the Dong Ha Bridge, in an endeavor so daring that it has become part of Marine Corps legend.

The bridge’s superstructure was a hulking construction that had been made by American Seabees. It was supported by six enormous I-beams three feet tall. To destroy it, Colonel Ripley would have to hand-walk and crawl 500 pounds of TNT and Plastic Explosives one hundred feet into its under belly. All the while, he would be submitted to continual enemy fire. His difficulties were multiplied by the sleep and food deprivation he had suffered throughout the previous days.

The feat was so difficult that no one believed survival, let alone successful completion, was possible. Nevertheless, after hours of intense physical exertion, everything had been put in place, the charges were detonated and the bridge was no more. Colonel Ripley was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions that day.

Some historians have argued that the destruction of that bridge was the single most important factor that postponed the defeat of South Vietnam until 1975.

However, there is another individual on whose shoulders the defense of South Vietnam during the Easter Offensive weighed heavily, but who has received insufficient historic recognition so far. That is why Mr. Botkin’s description of the role played by Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Turley is of particular value.

When the Lieutenant Colonel chose to return to Vietnam in 1971, there were only about one thousand Marines still on the ground. Since President Nixon’s policy of “Vietnamization” was fully underway, the brunt of the fighting was being born by Vietnamese soldiers. That is why Lieutenant Colonel Turley fully expected to see little if any action during this, his second tour.

His role as assistant senior Marine advisor would consist in helping senior Marine advisor Colonel Josh Dorsey and perhaps filling in for him from time to time. As such, he would live in Saigon, which, at the time, was far removed from combat. The closest he imagined he would come to actual fighting was an occasional and uneventful visit to the frontlines.

His expectations were shattered when, on a four-day visit to I Corps Tactical Zone, the Easter Offensive broke out. He happened to be at 3rd ARVN Division forward headquarters at Ai Tu when the Army officer in charge there began suffering nervous problems, abandoned his post and ordered Lieutenant Colonel Turley to take the helm.

Worse yet, communications with higher leadership in Saigon were practically nonexistent, meaning this change in command went unreported. In addition to facing the largest Communist advance of the entire war, Lieutenant Colonel Turley also had to confront hostile and mistrustful leaders, who continually second guessed his decisions and attempted to countermand many of his orders. The situation was so desperate, he was forced to take responsibility for disregarding some of the directives he received from higher-ups.

While other players in the offensive faced their predicament with the support of their leaders, expecting praise if they survived, Lieutenant Colonel Turley could only anticipate disciplinary action and perhaps court martial.

Diorama depicting Colonel John Ripley underneath the Dong Ha bridge located in Bancroft Hall at the United States Naval Academy.

Even when he ordered Colonel Ripley to destroy the Dong Ha Bridge, he did so against the direct wishes of his commanders. However, the reality of over two hundred tanks about to cross the Cua Viet River and invade South Vietnam was too dangerous for him to accept when he had the possibility to prevent it.

In spite of having no food, virtually no sleep and a severe case of dysentery, he faced the opposition of his superiors and stood by his post, directing air, naval and ground operations that salvaged a desperate situation. He continued in this capacity for a full four days until he was ordered back to headquarters for questioning. The physical, psychological and moral stress he faced during this time can hardly be imagined.

Nevertheless, he survived and emerged as one of the greatest examples of “honor and triumph” of the entire war.

The stories of these three heroes and much more are included in Rich Botkin’s Ride the Thunder. This makes it a must-read for all military-buffs, American patriots and especially those who are interested in knowing the true history of the Vietnam War – one not tainted by politically correct historians intent on criticizing America and especially its military.

However, readers should be warned that Mr. Botkin’s book, while less offensive than many military volumes, does have its share of profanity, which he mostly limited to the contents of direct quotes from characters in the book. Similarly, there are references, though not graphic, to those activities that have unfortunately been so closely linked with soldiers throughout history.

Nevertheless, Ride the Thunder is an exciting and highly informative read. No one’s military library is complete without it.

If you do not know about the Lion of Fallujah, you should. When staff writer Tony Perry went to Fallujah in 2004 to report on the war, he ended up writing a whole piece about one Marine instead. His name was Douglas Zembiec and the article was titled: Unapologetic Warrior. What Perry liked about Zembiec was how quotable he was. If you don’t have time to read the article below, you can at least relish the no nonsense manner in which this Marine responded when being interviewed:

“From day one, I’ve told [my troops] that killing is not wrong if it’s for a purpose, if it’s to keep your nation free or to protect your buddy,” he said. “One of the most noble things you can do is kill the enemy. These young Marines didn’t enlist to get money to go to college. They joined the Marines to be part of a legacy.”

What is not commonly known about this young man is that he looked to the late Col. John Ripley as a mentor. When I read more about Zembiec I noticed the striking similarities between the two men. Both displayed a ferocity on the battlefield which was almost unmatched and both were Catholics and both treated their men with respect.

“He’s everything you want in a leader: He’ll listen to you, take care of you and back you up, but when you need it, he’ll put a boot” up your behind, said Sgt. Casey Olson. “But even when he’s getting at you, he doesn’t do it so you feel belittled.”

Said Lt. Daniel Rosales: “He doesn’t ask anything of you that he doesn’t ask of himself.”

Like Col. Ripley he took time in the middle of battles to write condolence letters to the families of deceased Marines.

He also recommended individuals for combat commendations: “I’m completely in awe of their bravery,” he said. “The things I have seen them do, walking through firestorms of bullets and rocket-propelled grenades and not moving and providing cover fire for their men so they can be evacuated… ”

Zembiec was killed in action on May 10, 2007. He was 34 years old. May he rest in peace!

Col. John Ripley and his son Tom were the ones designated by Zembiec himself — should he die in combat– to deliver the message of his death to his widow Pamela.

To Read an interesting article about Zembiec, click here.